FULLERTON, CALIFORNIA: SEPTEMBER 18, 1968

It’s him, as sure as Hades, in her section of the Denny’s: Victor Malone, the boy she’d slept with in September, 1950. Ginny’d met him at The Pike, in uniform, in line behind her, clutching a quarter in his fist to take four snapshots in their photo booth. He’d been an Army private with orders to Fort Ord and then Korea. It had been his eighteenth birthday. His driver’s license proved it.

He’d been alone. He’d said, “Virginia, I might not be comin’ home.” They’d shared a five-day whirlwind tour, exploring Southern California, Knott’s, the Great White Steamer, Hollywood, and Griffith Park. Their last night beneath the stars at Tin Can Beach they’d both surrendered their virginity and kept each other warm.

At dawn, she’d watched him sleep. Struggled not to fall in love. Sunrise over Bolsa Bay greeted the sandpipers.

He’d awakened, fired up his Ford, driven to Long Beach.

At the Red Car station, he hadn’t even kissed or touched her cheek. He’d just said, “Thank you, ma’am,” and let her walk away.

Disappointed, Ginny wondered what she’d done to make him mad.

Two days later, he’d shipped out to Korea.

Ginny hadn’t gotten mad for years.

But on his birthday, here he is, predictable as Halley’s Comet, eighteen years later, exactly to the day. His scar-pitted muscled arms are typical of car mechanics. A pack of Camels fills a pocket of his ironed sun-bleached shirt with its Union 76 orange-and-blue Minuteman emblem. Above the right pocket, his name, in blue embroidered letters, “Vic.”

What? He thinks she has a duty?

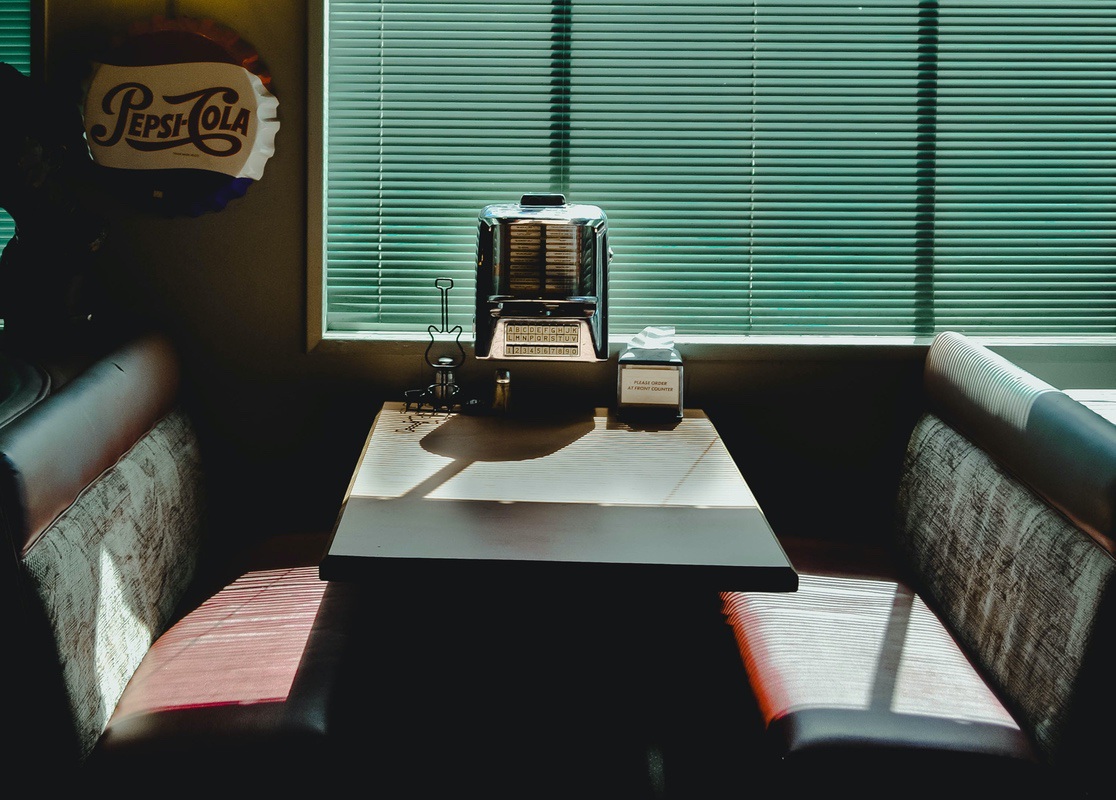

Well, she just doesn’t. She ignores him, stuffs her order pad and pen into her apron. At five a.m., he eats his “country-fresh fried eggs,” sips his “Denny’s Special Coffee” in her window booth. He’s not getting a freebie.

Any freebie. Not even his Denny’s birthday breakfast.

He broke her heart. She dreads even a peek into those eyes. Once, she’d thought she had found love there. Her innocence had cost her heart.

His innocence had gone to war.

Still, he’d written, “Miss you, Ginny.”

Thrilled, she’d written back, mailed those snapshots from the Pike, wearing her pink pullover sweater he’d said flattered her.

Every night in Buena Park, she’d checked her mailbox.

No letters.

After a year, she’d given up. Married Leonard for eighteen months until the bastard beat her up a second time.

Now, she keeps men at arm’s length. She’s convinced they only break things. Victor broke her heart, and her ex-husband broke her jaw. Best to preserve your heart in cold-storage. Stuff emotions. Play it safe.

She’d never known if Vic was dead or if he’d found another woman. She’d called the Pentagon. Of 37,000 damn obituaries, Victor Malone’s name wasn’t among them.

Now he shows up, wanting “coffee.” Screw him. He’s staring at a photograph. He hides it every time Ginny walks by. He glances at her. Ginny’s hoping Victor won’t remember. Maybe a stranger just resembles him.

A lot.

Save for a mess of ugly scars on his left cheek and a keloid where it seems Korea shredded off the bottom of one ear, scars as pink as Double Bubble.

One glance makes Ginny wince.

Victor brings his coffee to his lips.

He meets her gaze.

That photo strip he hides beneath his palm.

Snapshots from The Pike she’d mailed him in 1950!

“Virginia?” His voice is gravelly.

Shivers rifle up her spine.

She goes by Maggie, not Virginia now. In high school she’d been “Ginny.” She’s too slutty for Virginia. Magdalena seems more honest.

He sets his cup down on a napkin.

“Someone tell you I was here?” she asks.

“Coincidence.”

“Liar. It’s been eighteen years. Exactly.”

“You remember.” He looks away.

“Yup,” she says. “You never wrote.”

Virginia pours his coffee until it overtops his cup.

“I wrote two letters.”

“Funny, I only got one.”

“Well, there were two.” He’s staring at her hand. “Perhaps I wrote, but Uncle Sam’s Misguided Children never delivered my second letter.”

Her ring finger feels naked. His eyes look cloudy, as if he’s learned to cover pain beneath a thick haze of indifference.

Same way she has. She hides it better, if anybody cares.

Life has messed her up, same way it messed up Victor’s face. She’d been gorgeous when she’d climbed out of his slate-gray Ford Deluxe. It was the last time Ginny’d cried.

He looks away from Ginny’s memories. Typical.

She just wishes she knew how to release them.

NORTH OF HAGARU-RI, KOREA: 27 NOVEMBER, 1950, 1800-HOURS

Victor’s heard it on the radio from Tokyo. MacArthur’s predicting they’ll spend Christmas in Japan. The news cheers Regimental Combat Team RCT 31. They’ve battled since September. Hell might freeze, but soldiers smile, hoping war’s atrocity might end.

The axle underneath him jars his spine as they traverse frozen landscapes on roadways notched like shelves through treeless cliffs. Outside, winds howl. Riding a troop carrier with rustholes through the truckbed, Vic listens to weary fellow soldiers. It’s 35 below out, so cold the powdered snow mixes with dust in pale clouds, revealing their position.

Victor frowns and stomps to warm his toes.

He crams a fist into an armpit, blows air to thaw his other fingers. Exhales ice crystals.

“Cold enough?” somebody asks

He grunts. Stares out the back. The geniuses at headquarters don’t understand Korean winters. They’ve equipped troops with summer gear for their “mop-up operation.” Men wear everything they have, woolen undies, extra socks, pile jackets beneath wind-resistant parkas. Scarves are lashed around their heads, doubled-up over their ears beneath their helmets. Victor has no feeling in one ear.

At Hagaru-ri they left eight men at the Marine base, frostbite casualties. South Korean FNG’s, Fucking New Guys, took their places. Vic doubts they’ll survive unless this war wraps up by Christmas.

The motorcade stops. Army engineers repair the road. Freezing troops assemble outside, exercising to stay warm. The winter sears Vic’s lungs and makes his muscles burn.

He smells campfires. They will spend the night here.

For years, Ginny’s been angry. After topping off Victor’s coffee, she storms off. There’s a wall Ginny’s crafted out of ice she can’t break through.

She stops.

Why did Victor keep her picture?

Clearly, Vic hasn’t forgotten.

But he lied.

Ginny steels herself to find out why.

Men dig into position.

After chopping through ten inches of icy dirt, digging gets easy, few stones and fewer trees with any roots. The land is barren.

Colonel Faith sets a command post just behind their new perimeter.

After midnight, everything is quiet.

The first enemy probe occurs at 0100 hours. The Chinese fire, and men shoot back when they’re told not to.

That tells the Communists their army has encountered UN forces.

Chicoms melt away into the night.

Soon, thousands of Chinese on the ridgelines rain down mortar fire. They circle the right flank, firing American-made Tommy guns, seizing a mortar. Gaps form in the lines on the perimeter. Colonel MacLean calls for retreat. Vic trips over Chinese corpses and continues firing one shot at a time.

A grenade explodes.

The FNG in front of him collapses. Blood squirts out behind his knee. Moans attract enemy fire. Vic can’t reach him.

There must be thousands of Chinese, lighting hillsides with their gunfire.

That noisy FNG has died.

Daybreak reveals carrier-based Corsairs, counterattacking.

Antiaircraft guns shoot skyward.

For now, the Chinese can’t advance. Men shoot grenades to show the Corsairs where to bomb. It isn’t helping.Vic sprints into the encampment. Someone screams into the radio, “We have ourselves a Charlie-Fox,” Army-speak for cluster-fuck.

Victor bites his lip. He swallows terror.

Virginia clears her throat. “You want a warm-up on that coffee?”

He looks away.

“Been a long time, Vic,” she says.

She digs her fist into her hip. She isn’t sure whether to slap Victor or ask about the snapshots. A corner of the photostrip has fractured off like glass.

Ginny sucks her cheeks in. Those photographs. She looks so innocent!

Victor glances at her. Grins.

Ginny sees him swallow.

Hard.

Maybe Vic still has a soul, despite how badly he has wounded her.

She wonders if she has a soul herself.

While medics bandage up the wounded, one-hundred casualties lie on cots outside the aid station, and body bags are stacked like cords of wood.

A chopper thunders toward a rice paddy.

BOHICA, Vic thinks. Bend over, here it comes again.

Lieutenant General Ned Almond, commander of the X Corps, is paying one of his legendary visits. He strides toward the camp to have a chat with Colonel Faith.

Everybody stays out of his way.

A bugle call. The General would like a little ceremony.

All snap to attention.

General Almond retrieves three Silver Stars out of his pocket. He gives the first to Colonel Faith, selects two soldiers at random, pins medals to their parkas, then addresses all the men. “The enemy delaying you is nothing more than remnants of Chinese divisions fleeing north. We’re still attacking, and we’re going all the way north to the Yalu. Don’t let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen distract you.”

Almond climbs aboard his helicopter, ascending toward safety.

“Bullshit,” Colonel Faith mouths, tearing off his Silver Star. He throws it down into the snow, whirls to face his men. “Better get your positions in good tonight,” he mutters, “or there won’t be any positions tomorrow morning.”

“What did your second letter say?”

“The one I sent from the Marine base? Don’t remember.”

“Yes, you do.” She plops her coffeepot on the table and sits down. “I wrote I loved you in my letter. What did you write? After eighteen years, I need to know the truth.”

He looks down at her photos, not at her.

29 NOVEMBER, 0600-HRS

Chinese burp guns are butt-ugly, but they spread typhoons of lead. Their noise is the most frightening sound Victor’s ever heard. Brrrrrap-pap-pap-pap-pap-pap. Their racket echoes off the mountains. PPSh-41 submachineguns rain bullets into the encampment.

The men, now dug in deeper than a tick in a hound’s hide, receive orders to retreat while still engaging Chinese fire. One-hundred-twenty-seven wounded are loaded onto truckbeds leaving no room for equipment. They will leave it all behind, kitchen provisions, ammunition, medical supplies. If they burn it, fires will reveal their position. Chinese roam the barren mountainsides like colonies of ants.

Victor has a nasty feeling in his gut.

Soon, Chinese attack in successive human waves. Colonel Faith thinks he’s outnumbered, eight-to-one.

RCT 31 fights hand-to-hand, using bayonets and tools. No time to bury dead or help the wounded. Vic glances up to see three parachutes from Corsairs drop supplies, badly-needed food, and ammunition. But winds blow their supplies to Chinese outside the perimeter. Victor’s heart sinks.

He spots two Chicom infiltrators. Kills them.

Across a finger of ice along the edge of Chosin Reservoir, gunfire echoes from positions everyone assumed were friendly. Colonel MacLean hollers to stop, walking out onto the ice.

He’s hit.

He staggers, collapsing near the other side, disappearing into fog.

Shit, that wasn’t friendly fire!

Colonel Faith counter-attacks. Ice is littered with Chinese. Sixty-eight kills are confirmed. The road’s been cleared.

But there’s no trace of MacLean. They’re surrounded in a field, having ridgelines on three sides loaded with Chicoms. Fields of ice span Chosin Reservoir, their sole path of retreat.

And that reservoir ice won’t support their motorcade.

1 DECEMBER, 0900-HRS

Holed up in the same position 72 hours, over one-thousand are dead. Most surviving men are wounded. Due to unexpected weather, air support’s been discontinued.

Reinforcements still haven’t arrived.

There’s no more surgical equiment, no morphine, no bandages. Medics improvise with undershirts and towels. At 1100 hours, a Marine Corsair appears, radioing no reinforcements are en-route.

Colonel Faith informs his troops, “We’ll need to break through the perimeter. Dash to safety. Can’t afford to risk another night here. Select your twenty-two best vehicles. Leave the rest behind. We’re low on fuel. The dead will ride. Everyone else walks.”

They destroy their other vehicles with phosphorus grenades and form a column heading south. Victor walks beside a truck. On point, Company C mans a dual 40-millimeter halftrack.

Enemy bullets whistle past.

Friendly planes in close-support miss their target, dropping napalm onto the halftrack. It explodes. Men roll through snow, beating the flames out.

Colonel Faith rounds up survivors. A Chinese roadblock stops the trucks. Grenade fragments shred through Victor’s cheek. His blood is freezing. He fights on, joining eighty-some-odd men and Colonel Faith to clear the roadblock. But Faith is badly wounded.

They load the dying colonel into a truck cab.

The cold sun disappears.

They walk out onto the ice.

Victor staggers on by moonlight, needing something to believe in. Virginia’s snapshots are in his wallet, but if he removes his gloves he’ll lose his fingers.

Besides, he cannot see her in the dark.

2 DECEMBER, 0400-HRS

After an ambush of the fifteen trucks remaining, with no officers, no food or ammunition. winds have cleared snow from the ice. Victor races against time.

He needs to find Hagaru-Ri.

It’s on the shoreline. If he walks fast enough, he’ll find it.

Brrrrrap-pap-pap-pap-pap-pap. Bullets ricochet off ice.

He has no feeling in his legs. He’s touched his face. Something is wrong. He staggers toward a wounded soldier, throws the man across his shoulders. Tries to lift him, glad for warmth.

The sergeant coughs up blood.

“Don’t die on me, you bastard,” Victor whispers.

No pulse. No breathing.

“Dammit!” Victor says. The warmth from the dead mass has thawed his fingers just enough Victor fumbles for his wallet.

And that snapshot of Virginia.

Finding strength to stumble on.

Warmth he remembers.

He trudges south.

For hours.

The Marines tell him his unit faces court-marshall for desertion.

Marine General O.P. Smith hopes they’ll spend some time at Leavenworth. “A few laundrymen,” he says, “and you assholes cut and run.”

They have it wrong, but no Marine backs Army grunts against a two-star Marine general who dismisses the survivors. The damn Marines listened to Almond, who bullshitted MacArthur, got his troops overextended. Almond won’t admit his error.

Stunned, Victor has no recourse. He’s grieving friends, exhausted.

All his officers are dead. Not one soldier brought them home.

For three long years in other units Victor knows he’ll fight his best.

But henceforth, he’ll be branded a deserter.

She hopes to figure out what she did wrong, says, “You okay?”

He shoves the photostrip in her direction.

She asks again, “What did you write? I checked my mailbox for months. Did you ever write me back?”

“Ginny, I lied.” He takes a breath. “Never mailed my second letter.” He shivers, choking up. Evidently, one of Victor’s tears has melted.

“Dammit. I loved you.” She wants to slap him, but he’s finally told the truth.

“I was ashamed.”

“Ashamed of what?”

His head ratchets her direction as if he wills himself to face her. “I loved your memory.” He seems to peer into her soul like she remembers in the backseat of his Ford. “A Navy chaplain with the Marines claims we threw down all our weapons, cut and ran, abandoned two commanding officers to Chicoms. General Smith labeled us cowards. I don’t deserve you, Ginny Thomas.”

“Who in bloody hell is General Smith?”

“With the Marines.”

She leans forward. “Victor, please tell me what happened.”

“Don’t want to. Dammit, Ginny, I don’t want to.”

She cups Vic’s frozen hands inside her fists and meets his gaze, fearing he can see clear to Korea. Survivor’s guilt, combat fatigue. So many names civilians use for conditions they refuse to understand.

But as a woman who’s been battered, Ginny has a hint. If she reaches him, she rescues herself, too. “Tell me, Vic,” she whispers. “You didn’t come here to drink coffee. No one can reach us if we lock our doors and board up all our windows.”

He wraps his hands around her coffeepot. Stares toward the doors. His gaze returns to hers. “Buddies were scattered on the ice. Bodies stretched past the horizon, limbs black with frostbite.” Tears wet Victor’s cheeks, and he grates out, “The damn Chinese took all our shoes.”

He’s weeping now. She listens to the horror and the shame for forty minutes.

His hands are warm enough to finally touch her cheek.

She caresses his cheek, too. His keloid feels like a heart. His smile breaks, and she is back at Tin Can Beach, watching sandpipers and wishing she had somebody to share it.

“It’s your birthday,” Ginny whispers. “I’ll buy breakfast.”

“Isn’t it…free?”

“Perhaps we both are now, Vic. Ever been to Nu-Pike?”

Victor’s head shakes.

“My shift ended at seven. Can you drive?”

He takes her hand, escorts her to the front seat of his Ford.

It’s being restored. Restoration is a miracle, she thinks.

Victor cranks the V-8 engine. Drapes an arm across her shoulder.

She snuggles close.

He turns right onto Harbor, cruising south.

Ginny grins. It feels damn fine being warm.